Aside from how important queer representation in the media is, it’s also something that fascinates me. And part of that discussion, routinely, is who gets to play these characters. In an ideal world, where any queer person would be considered evenly for any role alongside cisgender and straight actors, that shouldn’t matter. But that’s not the world we live in. It stands to reason, that if transgender actors wouldn’t get considered for cisgender characters, the the reverse should be true. That’s often not the case even now. So, let’s take a moment to consider what it must have been like to be a transgender actor in the 1970’s.

Carol Byron was born in Balmain, New South Wales, Australia on September 2, 1943. She was assigned the male gender at birth and named “Richard” by a mother who ultimately abandoned her four months later, placing her child in the care of a woman named Hazel Roberts. Her new mother enjoyed teaching her song and dance routines. At eleven years old, however, her mother Evelyn came back into the picture with a new husband, and took custody of their son. This new stepfather physically abused their kid. Carol dropped out of school at 15 years old, and began working, taking a job putting makeup on mannequins and arranging the displays at David Jones. A year later, she ran away from home to avoid the abuse — but continued her job. At the age of seventeen, she took on the name Carol and began transitioning to live life as a woman.

She was arrested for crossdressing, but actually beat the charge based entirely on being flippant. Not a strategy I recommend, but when she came before the judge she asked what the “offensive behavior” was — the judge explained, dressing as a woman. And she responded, “You have a wig and robe on.” The case was dismissed.

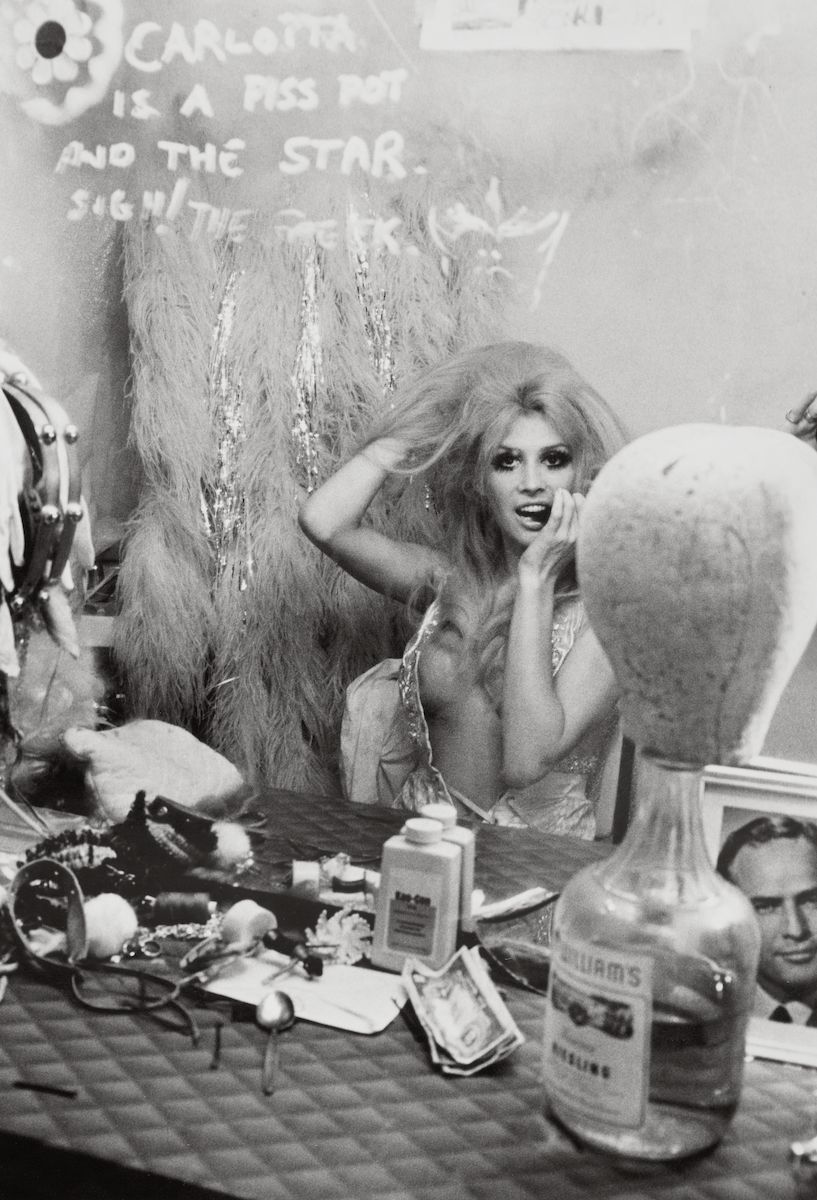

She took on the stage name Carlotta, apparently from Empress Carlota of Mexico (who I will admit I know almost nothing about) and set about establishing herself. About this time, Lee Gordon — an promoter with a resume that included names like Elizabeth Taylor and Judy Garland — was opening what may have been Australia’s first drag club, the Jewel Box Revue Club in King’s Cross, Sydney. They hired Carlotta as a performer. Before too long, the club changed its name to Les Girls Restaurant and kept Carlotta on for its Les Girls caberet act. The cast was advertised as exclusively men in drag, though some — like Carlotta — were transgender women. Carlotta quickly became the star of the show. Because of that, she earned the nickname “Queen of the Cross”. Although Gordon was no longer one of the owners at this point, he continued helping Carlotta as her manager.

In 1970, she had her first film appearance — credited as appearing as herself in a movie called The Naked Bunyip. This wasn’t exactly a big break, but it did open some doors. The movie was, apparently, fairly influential. One of those doors was for her to be cast as Miss Robyn Ross on a show called Number 96 — a show that had already broken ground with gay character Don Finlayson (played by Joe Hasham) the year before. The character of Robyn Ross was the new girlfriend of character Arnold Feather (played by Jeff Kevin), and appeared in four episodes in 1972. Ultimately, it was revealed that she was a transsexual showgirl — a fact which led to the end of the romance, and the end of her storyline on the series. Here’s her “coming out” scene — the language is, obviously, not what we would currently use. To keep this scene, and the end of this storyline a surprise, her scenes were all shot on a closed set and she was initially credited as “Carolle Lea“.

Four episodes, of course, doesn’t seem like a big deal. Especially on a soap opera, which churns out new episode practically every day. But these four episodes were a very big deal because they were the first time that a transgender person played a transgender character on television anywhere in the world.

Afterwards Carlotta decided to undergo sex reassignment surgery (also known, now, as a gender confirmation surgery). Prior to the surgery, a board attempted to cure her — putting her through torturous testing including electric shock therapy on her, though she tore the wires off of her. She also, reportedly, threw a shoe at the doctors engaging in the tests. The feisty outburst worked and she was able to get the surgery. She was not, as is sometimes reported, the first person in Australia to have the procedure. She was, however, the first person in Australia that was publicly reported as having the procedure.

Some time afterwards, she was invited to do a drag performance in London. She jumped at the opportunity, the show was hugely successful, but found she didn’t enjoy it and soon returned to Australia. Where she married a guy who’s name is nowhere to be found but since I see some places where her name is reported as Carol Spencer so I’m guessing his last name was Spencer. She tried out a life of “domestic bliss” as a housewife, but it doesn’t last too long.

Carlotta showed up on film again in 1982 playing Ron in a movie called Dead Easy. I don’t know if that character was transgender or not, it’s a fairly minor role and I haven’t seen the film.

In 1987, she toured New Zealand with a touring production of Les Girls. Short after that, her marriage ended — she left him so that he could have the opportunity to become a parent. So she resumed working at Les Girls until 1992. With her off and on career with them, she had performed with them for an impressive 26 years.

In 1994, she published her first book — He Did it her Way: The Legend of Les Girls with James Cockington. That was the same year the iconic movie The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert was released. Carlotta was one of the inspirations behind the movie — and it, in turn, inspired her. She attempted to start her own show: Carlotta & Her Beautiful Boys which launched in 1996. This was a popular show but not a financial success and ended up bankrupting her after three years.

But Carlotta is not a woman who can be kept down. In 1997, she began appearing as a recurring panelist on the show Beauty and the Beast. (I’m linking to the Wikipedia page on this one because, personally, I was a little confused when that didn’t have to do with fairy tales and talking furniture.) On the show, the panelists answer letters from viewers and Carlotta’s life up to that point made her invaluable to the show. Kids, particularly queer kids, from all over Australia wrote the show specifically in the hopes of getting her advice. Here’s a clip of her on the show in 2001 (not talking about queer issues though, I can’t find any clips of that.)

She was popular on Beauty and the Beast and that led her to more appearances as a television personality. In 2003, she appeared on the short-lived comedy talk show Greeks on the Roof. She also published another book, entitled Carlotta: I’m not that Kind of Girl. Two years later, Carlotta launched a show that was a half-million dollar production based on her recent book Carlotta’s KingsX. She subsequently appeared on Good Morning Australia and on the music quiz show Spicks and Specks.

Also in 2005, the cast of The Naked Bunyip reunited for a short video “In a Funny Sort of Way” which discussed the movie and its impact on Australian cinema. So, 2005 was a very busy year for Carlotta. In 2006, she appeared in four episodes of the documentary series 20 to 1. That was also the year that Australian National Portrait Gallery purchased a portrait of Carlotta and incorporated it into their collection.

Carlotta later launched a touring one-woman show called Carlotta: Live and Intimate. In 2013, she began appearing as a regular guest panelist on the morning news show Studio 10. The following year, a made-for-TV movie about her life was made called Carlotta. The film was criticized for only hinting at the harsher parts of Carlotta’s life as a transgender woman. Carlotta was played by cisgender actor Jessica Marais and while I would like to criticize that choice, but Carlotta was actually involved in the casting.

In 2018, she was diagnosed with bladder cancer. Her doctors caught it early, performed surgery, and she made a full recovery and jumped right back into her career. In 2019, she continued touring with her musical revue Carlotta: Queen of the Cross which features a wide variety of music, especially from other queer artists like Peter Allen (whom she had been friends with) and Stephen Sondheim.

On January 26, 2020 she was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for services to the LGBTQ+ community and to the performing arts. Although this is the most recent and most impressive recognition Carlotta has received for her decades of work, she’s also been recognized with the King’s Cross Award, the Drag Industry Variety Award (in 1997) and a Australian Club Entertainment Lifetime Achievement Award (in 2018). That last one may have to get given to her again, as Carlotta is still performing, and no doubt has much more that she will achieve.

As I mentioned, these aikāne were particularly encouraged in the rulers of Hawai’i — but that past tense is particularly relevant. This was particularly notable in the case of Kamehameha III (born as Kauikeaouli on March 17, 1814) who became king of Hawai’i in 1825 at eleven years old. As he was still fairly young, the real power remained in the hands of the kuhina nui (basically queen regent) Kaʻahumanu who had converted to Calvinism the year before. So for the first several years of his reign, the young and impressionable Kamehameha was torn between the traditions of his people, and the devout Calvinist Christianity of missionaries from the United States. Kamehameha was probably the first king of Hawai’i who was not actually encouraged to have aikāne. Furthermore, there’s a handful of records indicating the Ka’ahumanu had noticed Kamehameha eyeing boys and had been actively discouraging that.

As I mentioned, these aikāne were particularly encouraged in the rulers of Hawai’i — but that past tense is particularly relevant. This was particularly notable in the case of Kamehameha III (born as Kauikeaouli on March 17, 1814) who became king of Hawai’i in 1825 at eleven years old. As he was still fairly young, the real power remained in the hands of the kuhina nui (basically queen regent) Kaʻahumanu who had converted to Calvinism the year before. So for the first several years of his reign, the young and impressionable Kamehameha was torn between the traditions of his people, and the devout Calvinist Christianity of missionaries from the United States. Kamehameha was probably the first king of Hawai’i who was not actually encouraged to have aikāne. Furthermore, there’s a handful of records indicating the Ka’ahumanu had noticed Kamehameha eyeing boys and had been actively discouraging that. As a teenager, Kamehameha rebelled — in 1831, he publicly announced his aikāne with Kaomi, though the relationship wasn’t exactly new at this point. The missionaries did not like this because he had originally been a Protestant minister who abandoned his faith for this relationship (which they considered sinful), and a lot of Hawaiians didn’t like this because Kaomi was half-Tahitian. When Ka’ahumanu died in 1832, the council of chiefs attempted to install another kuhina nui — Kamehameha’s sister Kina’u. Instead Kamehameha declared that Kaomi was his ke-lii-ki (literally “entrenched king” but basically, joint ruler). Now, descriptions of the period of the next few years — called the “time of Kaomi” — make it sound super hedonistic, with the “return of evil ways that had been stamped out” and super corrupt with Kaomi “giving away land to landless men,” but the truth is probably that the “evil ways” were Hawaiian traditions like hula dancing and the “landless men” were commoners who the council were refusing to lease land to in favor of leasing it to wealthy people or people they especially liked (because that was a thing that had been happening). But under Kaomi’s co-rule, distilleries started brewing alcohol again so I guess that’s a little hedonistic (for the 1830’s).

As a teenager, Kamehameha rebelled — in 1831, he publicly announced his aikāne with Kaomi, though the relationship wasn’t exactly new at this point. The missionaries did not like this because he had originally been a Protestant minister who abandoned his faith for this relationship (which they considered sinful), and a lot of Hawaiians didn’t like this because Kaomi was half-Tahitian. When Ka’ahumanu died in 1832, the council of chiefs attempted to install another kuhina nui — Kamehameha’s sister Kina’u. Instead Kamehameha declared that Kaomi was his ke-lii-ki (literally “entrenched king” but basically, joint ruler). Now, descriptions of the period of the next few years — called the “time of Kaomi” — make it sound super hedonistic, with the “return of evil ways that had been stamped out” and super corrupt with Kaomi “giving away land to landless men,” but the truth is probably that the “evil ways” were Hawaiian traditions like hula dancing and the “landless men” were commoners who the council were refusing to lease land to in favor of leasing it to wealthy people or people they especially liked (because that was a thing that had been happening). But under Kaomi’s co-rule, distilleries started brewing alcohol again so I guess that’s a little hedonistic (for the 1830’s). Following the death of his lover, Kamehameha acquiesced to many more of the council of chief’s requests. Kina’u officially became kuhina nui, ruling alongside Kamehameha and taking on the name Kaʻahumanu II. In 1836, he married a woman named Kalama Hakaleleponi Kapakuhaili. He and Queen Kalama had two children, who both died as infants. Kamehameha went on to have several other affairs with both men and women, bearing twin illegitimate children (one of whom died, and one of whom he adopted and legitimized).

Following the death of his lover, Kamehameha acquiesced to many more of the council of chief’s requests. Kina’u officially became kuhina nui, ruling alongside Kamehameha and taking on the name Kaʻahumanu II. In 1836, he married a woman named Kalama Hakaleleponi Kapakuhaili. He and Queen Kalama had two children, who both died as infants. Kamehameha went on to have several other affairs with both men and women, bearing twin illegitimate children (one of whom died, and one of whom he adopted and legitimized). Kamehameha’s reign was pretty eventful from here on out (as if it hadn’t been already) — and long. Really long. In 1839, having learned about some of the Western ideas of law and government, he and several of his advisers created Hawai’i’s first declaration of human rights. They also crafted the Edict of Toleration which legalized Catholicism in Hawai’i — an act necessary to avoid a war with France. In 1840, they crafted Hawai’i’s first Constitution.

Kamehameha’s reign was pretty eventful from here on out (as if it hadn’t been already) — and long. Really long. In 1839, having learned about some of the Western ideas of law and government, he and several of his advisers created Hawai’i’s first declaration of human rights. They also crafted the Edict of Toleration which legalized Catholicism in Hawai’i — an act necessary to avoid a war with France. In 1840, they crafted Hawai’i’s first Constitution.

This was the last major event of Kamehameha’s life. American tourists discovered Hawai’i as a winter destination in the 1850’s, a handful attempted to spark rebellions against Kamehameha but none ever found the support they needed. A new Constitution was written in 1852, which he signed. He formally declared his neutrality in the Crimean War on May 16, 1854. In August, he negotiated but never signed a treaty of annexation which would have made Hawaii a state. And then, on December 15, he died. He ruled for 29 years and 192 days, making him the longest reigning king in the history of Hawai’i. In 1865, he was reburied in the Royal Mausoleum of Hawaii (because it wasn’t built yet when he died). On July 31, 2018 — as part of the ceremonies celebrating the 175th anniversary of the restoration of Hawaiian sovereignty at the end of the Paulet Affair — a twelve foot bronze statue of Kamehameha III was unveiled in Thomas Square.

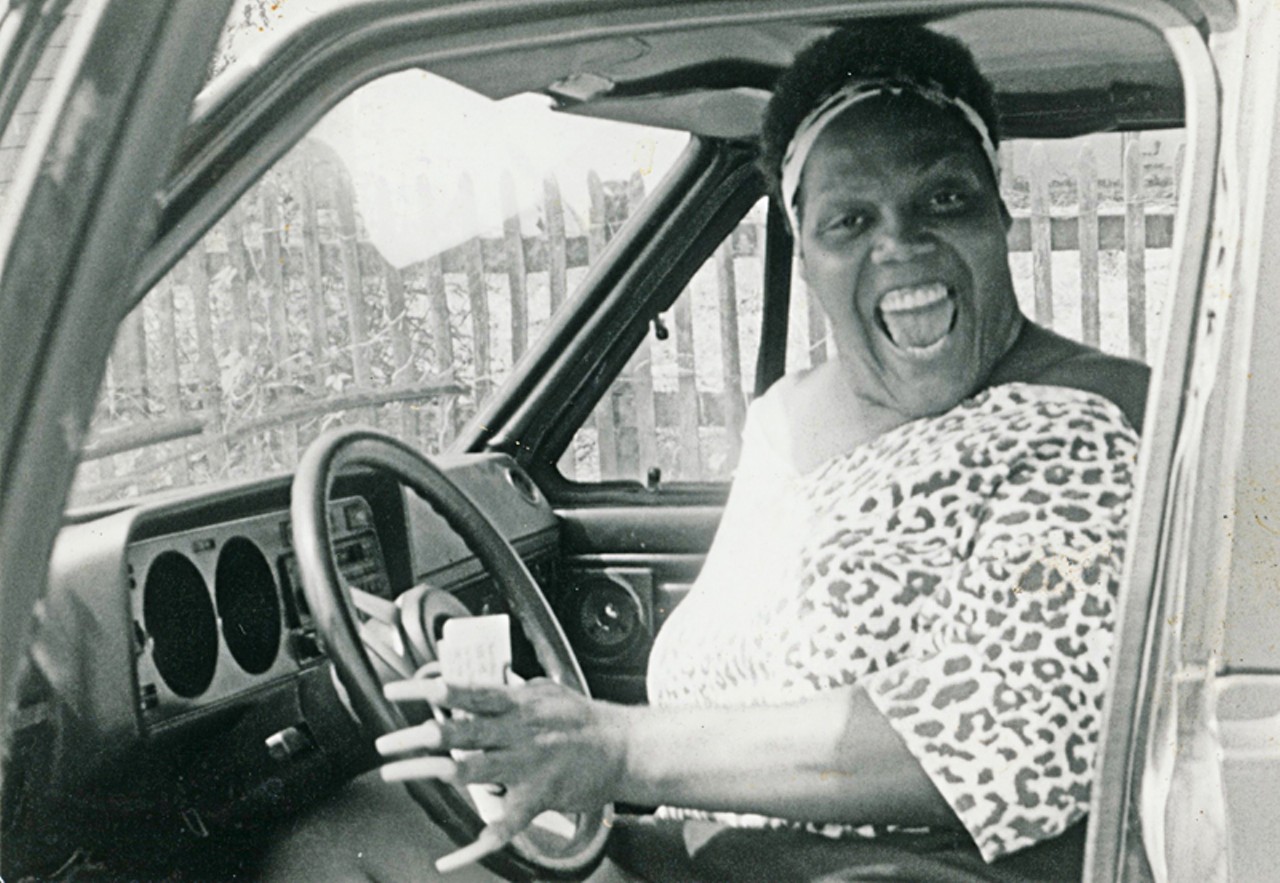

This was the last major event of Kamehameha’s life. American tourists discovered Hawai’i as a winter destination in the 1850’s, a handful attempted to spark rebellions against Kamehameha but none ever found the support they needed. A new Constitution was written in 1852, which he signed. He formally declared his neutrality in the Crimean War on May 16, 1854. In August, he negotiated but never signed a treaty of annexation which would have made Hawaii a state. And then, on December 15, he died. He ruled for 29 years and 192 days, making him the longest reigning king in the history of Hawai’i. In 1865, he was reburied in the Royal Mausoleum of Hawaii (because it wasn’t built yet when he died). On July 31, 2018 — as part of the ceremonies celebrating the 175th anniversary of the restoration of Hawaiian sovereignty at the end of the Paulet Affair — a twelve foot bronze statue of Kamehameha III was unveiled in Thomas Square. Although she regularly said her middle initial stood for “Pay it no mind”, Marsha P. Johnson proved to be a difficult person not to notice. Though Johnson is commonly referred to using female pronouns (she/her/hers) — and I’ll be doing that here — her actual gender identity is a bit of a mystery. She variously described herself as gay, a transvestite, and as a (drag) queen — though words like “transgender” really weren’t being widely used yet during her lifetime. My personal opinion is that she would probably identify as gender non-conforming or non-binary, but make your own judgments.

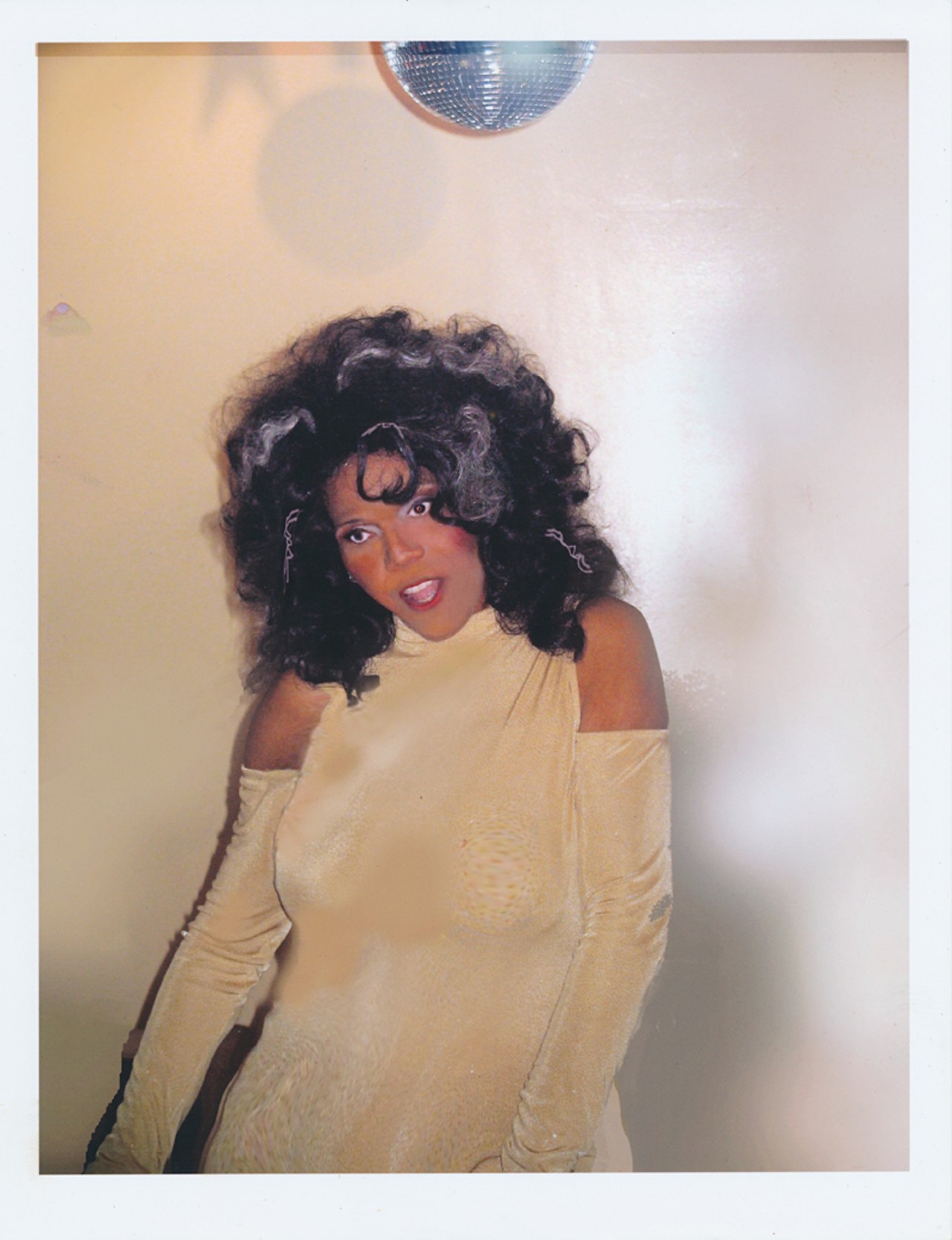

Although she regularly said her middle initial stood for “Pay it no mind”, Marsha P. Johnson proved to be a difficult person not to notice. Though Johnson is commonly referred to using female pronouns (she/her/hers) — and I’ll be doing that here — her actual gender identity is a bit of a mystery. She variously described herself as gay, a transvestite, and as a (drag) queen — though words like “transgender” really weren’t being widely used yet during her lifetime. My personal opinion is that she would probably identify as gender non-conforming or non-binary, but make your own judgments. She also began to perform as a drag queen — initially going by the name “Black Marsha” before settling on Marsha P. Johnson. She was often recognizable for having flowers in her hair — something she began doing after sleeping under flower sorting tables in Manhattan’s Flower District. She usually had on bright colored wigs, shiny dresses, and long flowing robes. Marsha was known to be peaceful and fun, but there was a violent and short-tempered side to her personality (which her friends commonly called “Malcolm”) — leading some to suspect that she suffered from schizophrenia. Between her sex work and her occasional violent outbursts, Johnson claimed to have been arrested more than a hundred times.

She also began to perform as a drag queen — initially going by the name “Black Marsha” before settling on Marsha P. Johnson. She was often recognizable for having flowers in her hair — something she began doing after sleeping under flower sorting tables in Manhattan’s Flower District. She usually had on bright colored wigs, shiny dresses, and long flowing robes. Marsha was known to be peaceful and fun, but there was a violent and short-tempered side to her personality (which her friends commonly called “Malcolm”) — leading some to suspect that she suffered from schizophrenia. Between her sex work and her occasional violent outbursts, Johnson claimed to have been arrested more than a hundred times. In 1973, Johnson also performed with the Angels of Light drag troupe — taking on the role of “The Gypsy Queen” in their production of “The Enchanted Miracle”. That same year both Johnson and Rivera were banned from participating in New York’s gay pride parade — the committee organizing the parade felt that drag queens and transvestites brought negative attention and gave the cause “a bad name.” In response, Rivera and Johnson marched ahead of the beginning of the parade.

In 1973, Johnson also performed with the Angels of Light drag troupe — taking on the role of “The Gypsy Queen” in their production of “The Enchanted Miracle”. That same year both Johnson and Rivera were banned from participating in New York’s gay pride parade — the committee organizing the parade felt that drag queens and transvestites brought negative attention and gave the cause “a bad name.” In response, Rivera and Johnson marched ahead of the beginning of the parade. In 1975, Andy Warhol took pictures of Johnson for his “Ladies and Gentlemen” series. Johnson’s success as an activist and a performer, as well as her regular appearances throughout the decade, earned her the nickname “Mayor of Christopher Street.”

In 1975, Andy Warhol took pictures of Johnson for his “Ladies and Gentlemen” series. Johnson’s success as an activist and a performer, as well as her regular appearances throughout the decade, earned her the nickname “Mayor of Christopher Street.”

During the 90’s, after many years of this, she developed an infection in her leg that ultimately put an end to her travels. She was admitted to a hospital in Bolzano, and afterwards stayed in a newly opened homeless shelter for women that had recently opened there. In 2012, she was given a place to stay at the Villa Armonia nursing home in the same city. Mariasilvia was not eager to give up her freedom, and adamantly refused to do anything but sleep inside the nursing home for the first three years then. After those first years though, she warmed to the idea and began to participate in picking the movies for theme nights, having meals with the other residents, and taking pictures of them all. Eventually, she even gave the books she had been traveling with for decades to the nursing home’s library. She remained there until she passed away at 83 years old on October 31, 2018. She died still estranged from her family and, sadly, forgotten by many despite the momentous act that cost her so much.

During the 90’s, after many years of this, she developed an infection in her leg that ultimately put an end to her travels. She was admitted to a hospital in Bolzano, and afterwards stayed in a newly opened homeless shelter for women that had recently opened there. In 2012, she was given a place to stay at the Villa Armonia nursing home in the same city. Mariasilvia was not eager to give up her freedom, and adamantly refused to do anything but sleep inside the nursing home for the first three years then. After those first years though, she warmed to the idea and began to participate in picking the movies for theme nights, having meals with the other residents, and taking pictures of them all. Eventually, she even gave the books she had been traveling with for decades to the nursing home’s library. She remained there until she passed away at 83 years old on October 31, 2018. She died still estranged from her family and, sadly, forgotten by many despite the momentous act that cost her so much. Garrison was born in Hahira, Georgia on October 7, 1940. At nineteen years old — still living in the closet as a man — Garrison moved to Boston to attend beauty school — but it turned out she didn’t like being on her feet all day. So she enrolled at Newbury Junior College and earned an associate’s degree. She followed that by attending Suffolk University and earning a B.S. in business administration, and then an M.S. in management from Lesley College. After this, she got a certification in management from Harvard University. Afterwards, she decided she didn’t actually need to attend every college in the Boston area, and didn’t earn any more degrees.

Garrison was born in Hahira, Georgia on October 7, 1940. At nineteen years old — still living in the closet as a man — Garrison moved to Boston to attend beauty school — but it turned out she didn’t like being on her feet all day. So she enrolled at Newbury Junior College and earned an associate’s degree. She followed that by attending Suffolk University and earning a B.S. in business administration, and then an M.S. in management from Lesley College. After this, she got a certification in management from Harvard University. Afterwards, she decided she didn’t actually need to attend every college in the Boston area, and didn’t earn any more degrees. I hope that almost anyone reading this site knows at least something about Matthew Shepard — whose face became a figurehead in the gay rights movement after his grisly murder in 1998.

I hope that almost anyone reading this site knows at least something about Matthew Shepard — whose face became a figurehead in the gay rights movement after his grisly murder in 1998.